Lorenzo Denicolai, PhD

University of Turin

Elisa Farinacci, PhD

University of Bologna

Through this brief article, we wish to present some preliminary considerations on contemporary forms of communication among Millennials and Generation Z in Italy. More specifically we will discuss two popular social networks that focus on video making and sharing: YouTube and TikTok. The topic of this article was presented at the conference “Lingue e Llguaggi del

Since 2005, Youtube’s claim has been ‘Broadcast Yourself’ which represents the main purpose of the platform. Nonetheless, today Youtube is more: according to Omnicore Agency, Millenials prefer YouTube two to one over traditional television and 37% of the 18-34 y.o. users are binge-watching and more than half of all views are from mobile phones. YouTube (YT) is the second most visited site after Google. Today YT has also become a search engine.

Nowadays, Youtubers (YTrs) are protagonists of YT’s environment. The rising phenomenon concerns a varied audience, but it seems to have a considerable hold especially on Millennials; at the same time, the

Our research aims to analyze the YTrs and Musers’/TikTokers typologies of productions and how these videos could be enjoyed by the Millennials’ audience. We started to analyze some of the most influential YTrs’ products (above all in the Italian context) and we focused on several cases: particularly, we considered “MecontroTe” (4,1 mln of followers); “Favij” (5,4 mln); “St3pny” (3,9 mln); “The Show” (2,8 mln); “Youtubo anche io” (270,000).

We will highlight some structural, linguistic and narrative elements that could be

Thus, we want to summarize our brief analysis through three keywords:

LANGUAGE: Each YTr ideates and develops a specific language for characterizing his/her own performances. Transmedia

SERIALITY AND CHALLENGES: Each YTr develops several serialities that characterize his/her channel. Many videos are about video games (YTrs are also called ‘gamers’): these products are a mix between tutorials and experiential videos in which the

COMMUNITY: Each YTr builds and represents a community of followers who contribute to broadening his visibility. In this way, the

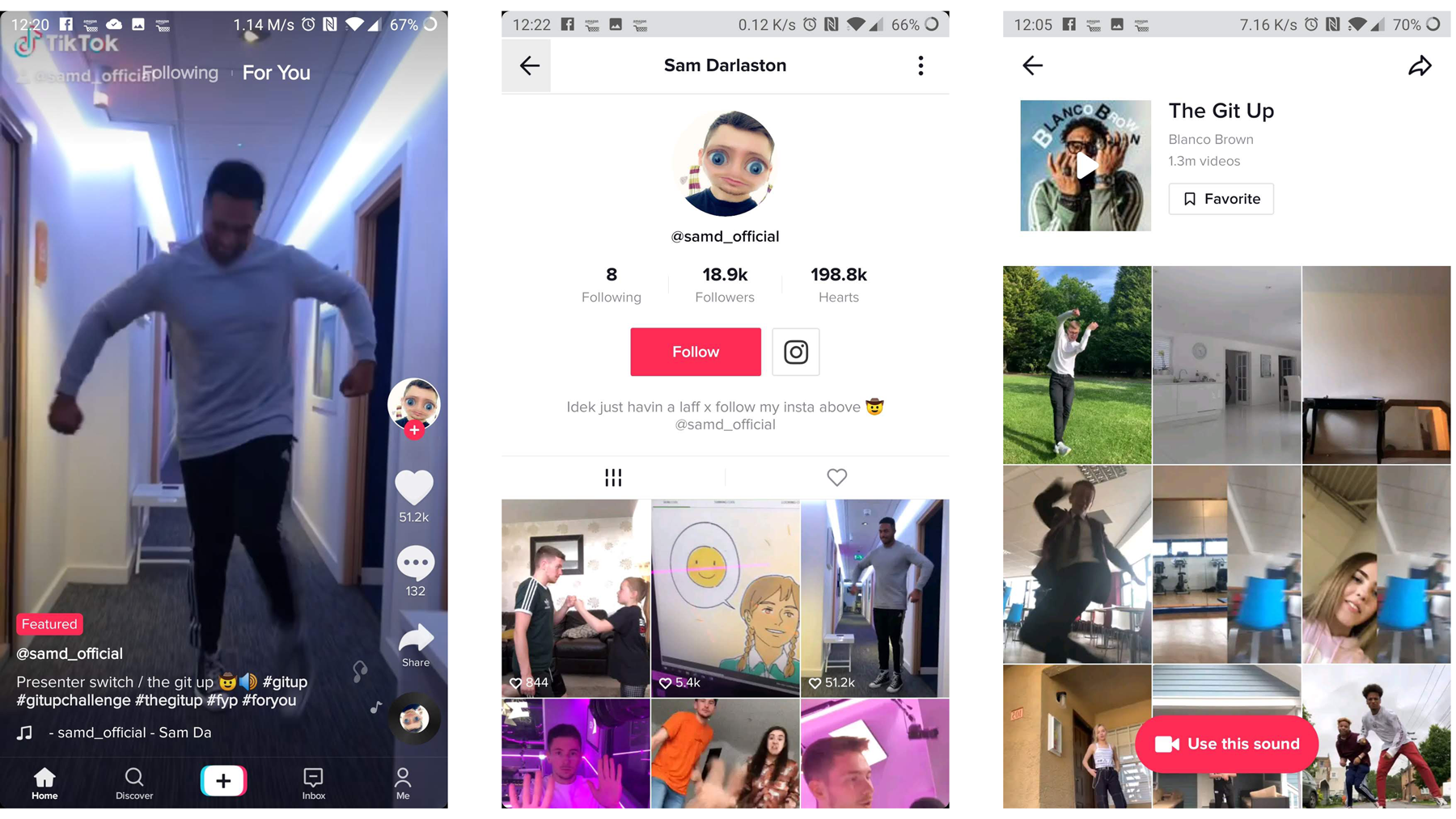

Let us know move to another social network that has invaded the Millennials’ and GenerezionZ’s mobile devices: TikTok.

“YouTube maybe Down, but TikTok is alive, awake and Never Better #StayWoke #YouTubeDown #MakeSocialFunagain” stated the extensive launch campaign of TikTok: the world-leading platform for short videos. It appears that YouTube’s longstanding tagline “broadcast yourself” is slowly being replaced by another motto: TikTok’s “Make every second Count”. The frontiers of videomaking and video sharing are reaching new speeds with this endemic new Social Network: if our attention span was already reduced to 2-3 minutes per clip, now the “seconds that count” are 15 (up to 60 seconds if you connect more than one clip together).

TikTok, or in the original Chinese Douyin meaning vibrating sound, is a video sharing social network created in 2017 from the acquisition by TikTok developers “ByteDance” of the already popular lip-syncing app Musical.ly. This social network, firstly spread among tweens and teens, is now widespread also among millennials and “Generation Z” users: it has been downloaded over 1 billion times (96 million in the US and 2.4 million in Italy) and it is available in 154 countries and 75 languages.

Numerous are the “parental instructions” appearing on the web in support of clueless parents who keep hearing their children raving about this app. Let’s adventure in this world discussing a few of its features through three keywords: PORTABLE, CREATIVE, DECENTRALIZED.

PORTABLE.

CREATIVE. The videos might be only 15 seconds long, but don’t let this fool you: there is a lot of work and planning involved in the production of these videos. Like Snapchat, TikTok has an array of AR effects that can be used in videos to change eyes or hair color; a World tab that gives you options to modify the environment; special effects specifically designed to be used on cats and dogs; the Beauty button that correct any esthetic imperfection; and a variety of filters, etc. In addition to this variety of editing tools,

DECENTRALIZED. It’s a decentralized network of performers with a distinctive social structure. TikTok is like “a never-ending variety show” and an experience of “pure entertainment” that in some cases may appear as the glorification of

We believe that these preliminary findings raise several questions that interest both media studies scholars, and pedagogy scholars. There are several issues at stake with both social networks: (1) They are both the results of the evolution process that all communication forms are going through, specifically Henry Jenkins definition of “Bedroom Culture”; (2) They constantly cross and confuse the already thin boundaries between virtual and real; (3) They are developing a platform-specific language that is unintelligible for outsiders; (4) They trigger identity dynamics that play on the combination of imitation differentiation strategies, that is they follow successful canons while at the same time they try to convey their own perspectives and personality.

Lorenzo Denicolai,

PhD , is research-fellow and professor of Media Anthropology at the University of Turin. His research interests concern audiovisual media, the man-technology relationship, and robotics. He coordinates a research project on audiovisual communication with aphasic people. He is the author of numerous academic papers and two monographs: Scritturemediali . Riflessioni,rappresentazioni edesperienze mediaeducative (Mimesis, 2017, with Alberto Parola) and Mediantropi. Introduzione alla quotidianitàdell’uomo tecnologico (FrancoAngeli, 2018). For contact information visit the University of Turin faculty page.Elisa Farinacci,

PhD , research-fellowship in Cinema, Photography,and Television at the Department of Arts (DAR) of the University of Bologna. She earned ajoint PhD degree in History (M-STO/06) at the Department of History and Cultures of the University of Bologna and in Cultural Anthropology (M-DEA/01) at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. At the Department of the Arts she is working on the project “Global Italy: Circulation and reception of contemporary Italian reality in European countries”. She is also collaborating with the Research Center on Media Education, Information and Education Technology (CREMIT ) of the Catholic University of Milan. For contact information visit the University of Bologna faculty page.

![[GLOBAL CREMIT] YouTube and TikTok: Audiovisual Languages of Everyday Life](https://www.cremit.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/tiktokYT.jpg)