Alessandra Carenzio

(Università Cattolica di Milano)

Simona Ferrari

(Università Cattolica di Milano)

The MEC conference held in Rovaniemi at the end of September 2021 has been a great opportunity to share knowledge and to discuss ongoing researches. The conference featured more than thirty presentations on four main topics: MEDIA, DIGITAL AND INFORMATION LITERACIES; DIGITAL MEDIA IN TEACHING AND LEARNING; PLAYFUL LEARNING; MEDIA EDUCATION, PARTICIPATION AND WELL-BEING

As CREMIT representatives, we presented the sresearch Older people’s media repertoires, digital competences and media literacies: A case study from Italy, conducted in partnership with Päivi Rasi from Lapland University and visiting professor at our university.

Digital media are part of everyday life and have an intergenerational appeal, entering older people’s agenda, practices and habits. Many people over the age of 60 lack adequate digital competences and media literacies to support learning, well-being and participation in society, thus calling for a discussion on older people’s willingness, opportunities and abilities to use digital media.

The study explores older people’s media use and repertoires, digital competences and media literacies to promote media literacy education across all ages. We discussed the data from 24 interviews conducted in Italy with people ranging from 65 to 98 years of age trying to answer the following research questions: what kinds of media repertoires emerge? What kinds of competences and media literacies can be described? What kinds of support and training do older people get and wish to receive?

The data was acquired through a method that we conceptualised as a “warm intergenerational interview” (Bakardjieva). We recruited students enrolled in the Master’s Degree Programme in Media Education at the Catholic University of Milan to conduct interviews with older people. From a media literacy education perspective, we consider the interview as a pedagogical action, which is based on intergenerational interaction and aims to promote both the interviewees’ and the interviewers’ media literacies. As Gubrium and Holstein noted at the end of the 1990s, the interview as a research method has become a means of contemporary storytelling, where people divulge life accounts in response to interview inquiries. The life storytelling approach is fundamental, above all, for older people to express and make sense of the digital world.

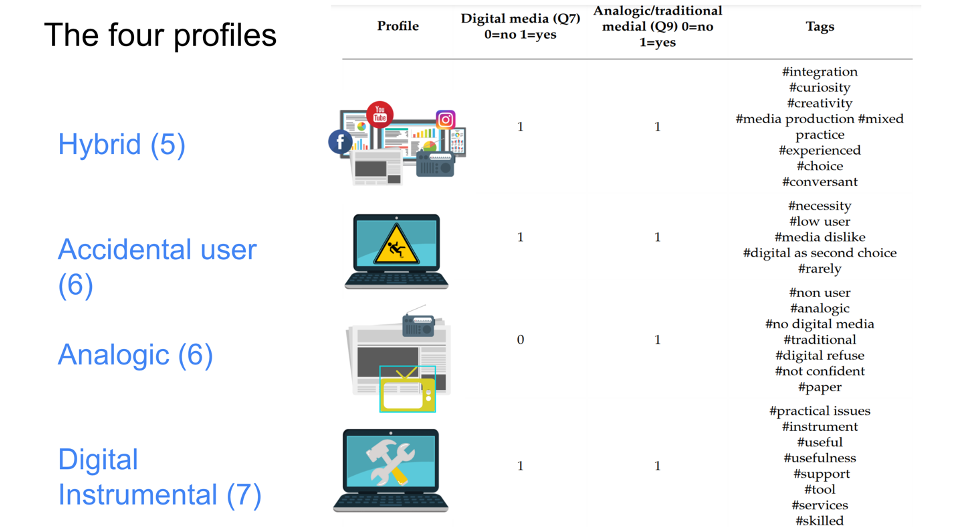

The analysis of the data produced four specific profiles concerning media repertoires: the analogic, the accidental, the digital-instrumental and the hybridised users. Media literacy is still a critical framework, but the interviewees were open to opportunities to improve their competences. The use of digital media has received a strong boost due to the pandemic, as digital media have been the only way to get in touch with others and carry out their daily routine.

Let’s see how these profiles appear. Theanalogic profile is based on a definite analogic media repertoire dominated by newspapers, television and radio with no expansion to the digital world. The accidental user profile came to use digital devices just by chance, for example, when there is nothing interesting on TV and they have no specific interest or skills. The digital-instrumental profile includes a relatively broad use of digital technologies and the internet, especially to meet specific practical needs linked to bank issues or payments and the use is very goal-oriented (travelling, shopping etc.). Finally, the hybridised profile manifests clearly hybridised media repertoires with an assortative integration of digital and traditional media in daily practices. This is interesting because it reveals a specific focus: someone who chooses media devices and services and consciously moves from one to the other and knows how they work.

Our sample is quite balanced if we consider the mix of media uses and the meaning of the media themselves (material and emotional contexts). The hybridised profile is representative of a minority (5), followed by the accidental user profile and the analogic profile (6 each), followed by the digital-instrumental (7), especially if we consider the massive use of smartphones and the internet via mobile devices.

Age is a variable, but not so clearly: it is evident in the analogic profile, quite important in the hybridised profile and very balanced in the other profiles.Six people were strictly analogic (no smartphone, just an old mobile phone and just for talking, no internet and no other digital media, with a declared analogic practice and somehow a very far idea of technologies and the internet). They are all female and aged over 73 years (except for one), and comment on their repertoires, for example, in the following way: “I really never thought to use them (other digital media), also because I don’t need them” (65, female). The accidental user profile is represented by six people, while five people correspond to the hybridised profile.

References

Baily, C. (2009). Reverse intergenerational learning: A missed opportunity? AI & Society, 23, 111– 115.

Bakardjieva, M. (2005). Internet society: The Internet in everyday life. Sage.

Bakardjieva, M., & Smith, R. (2001). The internet in everyday life: Computer networking from the standpoint of the domestic user. New Media & Society, 3, 67–83.

Brown, L. E., & Strommen, J. (2018). Training younger volunteers to promote technology use among older adults. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 46(3), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12254

Carenzio, A., Ferrari, S., & Rasi, P. (2021). Older people’s media repertoires, digital competences and media literacies: A case study from Italy. Education Sciences, 11, 584. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/11/10/584

Gall, M. (2014). Intergenerational learning between teenagers and seniors with the help of computers. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116(2014), 1274–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.382

Gamliel, T. (2016). Education in civic participation: Children, seniors and the challenges of an intergenerational information and communications technology program. New Media & Society, 19(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816639971

Hobbs, R. The state of media literacy: A response to Potter. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2011, 55, 419–430.

Kangas, M., & Rasi, P. (2021). Phenomenon-based learning of multiliteracy in a Finnish upper secondary school. Media Practice and Education. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/25741136.2021.1977769

Kupiainen, R. (2009). Lasten mediasuhteet mediakasvatuksen kysymyksenä. In S. Kotilainen (ed.) Suhteissa mediaan [In relationships with media] (pp. 167–183). Nykykulttuurin tutkimuskeskuksen julkaisuja 99. University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Lee, O. E.-K., & Kim, D.-H. (2018). Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(7), 786-795.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731518810798

Patrício, M. R., & Osório, A. (2016). Intergenerational learning with ICT: A case study. Studia Paedagogica, 21(2), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2016-2-6

Rasi, P., Vuojärvi, H., & Ruokamo, H. (2019). Editorial. Media education for all ages. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 11(2), 1–19.

Rivoltella, P.C. Nuovi Alfabeti; Editrice Morcelliana: Brescia, Italy, 2020.

Strom, R., & Strom, P. (2011). A paradigm for intergenerational learning. In M. London (ed.), The Oxford handbook of lifelong learning (pp. 133–147). Oxford University Press.

Tambaum, T. (2017). Teenaged Internet tutors’ use of scaffolding with older learners. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 23(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971416672808

Tuominen, S., & Kotilainen, S. (2012). Pedagogies of media and information literacies. UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education. https://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214705.pdf